What Wasn’t There: Archival Reflections from the Quai Branly Museum

- shadyradical

- Aug 1, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 2, 2025

On July 22, 2025, I found myself sipping espresso on the garden terrace of the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, laptop open, writing surrounded by the hum of languages and the looming Eiffel Tower in the distance. I came not just to admire it—but to interrogate it. I wanted to know what this major ethnographic institution held from Tanzania, specifically the Swahili Coast, and the long memory of Bagamoyo. I was there for a purpose—not just as a visitor, but as a cultural worker and archivist seeking.

I searched and searched for Tanzania. And found… nothing.

The Archival Ache of Absence

The Africa section of Quai Branly is grand and atmospheric. Yet it mirrored a longstanding archival pain: the places and people most intimately tied to cultural survival are often missing, misnamed, or misplaced in the global record. I found rich displays of West African art—like this brilliantly woven kente-like textile from Togo:

I found carvings and ritual figures from Mali (Bamana), Guinee (Malinke), Cameroon (Peul), Nigeria (Namji) and Lesotho (Sotho), each labeled with ethnic group, material, donor, and accession number:

The only object I saw from the Swahili region was this lone doll from the Turkana people of Kenya:

The only contextual information available was that it was donated by J. Roumeguere-Eberhardt. What year is this from, what was it used for, and what were the terms that the donor inherited it. Removed from context and presented in isolation, felt more like a placeholder than a presence.

The Archive as Mission

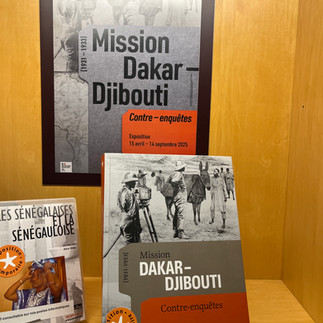

This exhibition chilled me to the core:

“Mission Dakar-Djibouti: Counter-Investigations”

This was a 1931-1933 ethnographic expedition through 14 contemporary countries (Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Benin, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Camerioon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti) to collect “African culture” for French institutions. It was an archival mission rooted in conquest—field notebooks, voice recordings, photos of men and women stripped of agency and context, carried out by African and French Scientists. I recognized a name from my own training, Marcel Griaule, the ethnologist who led this mission. This mission was supported by the Institut Td'Ethnologie and the Musee d'Ethnographie du Trocadero in Paris. Today, Musée du Quai Branly attempts a “counter-inquiry,” but the original logic remains: to possess, categorize, display.

The Mission Brought Back:

3,600 objects

6,600 natural specimens

370 manuscripts

70 human remains

6,000 photographs

3,500 metres of film

200 sound records

15,000 field notes

As I walked through, I wondered: What is the difference between this expedition and the kind of archival work I am doing in Bagamoyo?

When Archiving Feels Like Colonizing

I was trained in western archival practices. I use digital tools. I write metadata. I create infrastructure to preserve and protect cultural expression in Bagamoyo. But even with love, intention, and community trust, I often question my role.

Am I preserving, or am I extracting?

Who owns the recordings I collect?

Can I build a community archive without reinscribing colonial dynamics?

What happens when I leave?

There is deep structural asymmetry between me—with my funding, tech, and training—and the Tanzanian artists, elders, and youth who are often unable to re-access the materials when the digital storage devices purchased to store the performances and other digital materials stop working.

The Archive We Must Build

Quai Branly is a striking museum. Its architecture bends with ambition, and its lighting glows with reverence. But it also tells the story of how much has been taken, and how much has yet to be returned—not just physically, but spiritually, but epistemologically.

The Swahili archive lives.

Even if it is not on display.

Even if no glass case reflects its beauty.

We are building it. In classrooms and kitchens. Through drumbeats, dances, and oral histories. Through practices that refuse to let memory be stolen or stilled.

Sitting in the Library with My Questions

After wandering through the galleries, I sat quietly in the museum’s reading room. Around me, children sketched with crayons and colored pencils, laughing with facilitators, engaging with pieces of art and culture they may not yet fully understand.

And I wondered:

What are we teaching them about the archive?

What stories are being passed down about history, conquest, and representation?

Would I bring my daughter here? What would I want her to know—not just about what’s on the walls, but what’s been left out?

I imagined her walking through these galleries. Would she feel pride? Curiosity? Would she see herself? Would she sense the power dynamics buried beneath the glass?

And I imagined us sitting side by side, reflecting not just on the objects, but on the absences. On the systems. On the silences. On the need for an archive that remembers us differently.

How We Fit Into the Story

Museums like Quai Branly reveal as much about Europe’s past as they do about the cultures they attempt to display. They teach with light and space, but also with omission. And so I left carrying a question I still haven’t answered:

How do I, and how does my daughter, fit into this story of preservation and power, of memory and making?

What I know is this: we are not just witnesses. We are builders. We are archivists. We are mothers and daughters walking through rooms of history, daring to ask who wrote the labels—and who might rewrite them.

The Swahili archive exists—even when it’s not on the walls.

And we are the ones keeping it alive.

Comments